NEWS

NEWS  100P Airplane

100P Airplane  Bugatti

Bugatti  de Monge

de Monge  Organisation

Organisation  Pegasus Newsletter

Pegasus Newsletter Contact

Contact  Links

Links Main

Main

NEWS

NEWS  100P Airplane

100P Airplane  Bugatti

Bugatti  de Monge

de Monge  Organisation

Organisation  Pegasus Newsletter

Pegasus Newsletter Contact

Contact  Links

Links Main

Main

December 30, 2017 On December 11, the NTSB released a follow-up to the earlier factual report (see below news item of november 27), Investigator in Charge being Edward F. Malinowski. In this final report the probable cause is given, which was not included in the factual report: Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: You can download the final report here. We know from the investigation by the Le Rêve Blue team, that the engine anomaly in question was clutch slippage, apparently a conclusion which the NTSB does not want to publish (Maybe lack of factual proof?). The NTSB also opened a "Information Docket", a file center with all background studies, which can be found on https://dms.ntsb.gov/pubdms/search/hitlist.cfm?docketID=60586&CFID=1420135&CFTOKEN=2ab0ff50c406815b-83AA2D57-A4D0-E419-F9C5FAF76CDC7FFF. In this is the following information:

|

November 27, 2017

|

The NTSB has, as of last week, released the final report on the crash that occurred on August 6, 2016. The report is publicly available on the NTSB website. The Accident ID number is CEN16FA307. With the release of the report, we are now able to comment on the many questions we have received about the cause of the accident. It is clear that there was a loss of power to the forward propeller, this is documented by the GoPro cameras that were mounted in the cockpit and is consistent with the eyewitness accounts. Having analysed the cockpit video, the external video and the wreckage, the only reasonable conclusion is that the power failure in the forward engine drive train was the result of a clutch failure in the forward engine. The degradation in the power transfer from the engine to the propeller is demonstrated clearly by the engine RPM increasing while the air speed and rate of climb remained steady at first and then degenerated. To be clear, the NTSB did not analyse the engines or their integral clutches, so it is the Bugatti 100P team that has drawn this conclusion as the only logical explanation. The power failure occurred gradually, just after the aircraft became airborne, but appeared to become progressively worse (possibly to the point where there was no thrust provided by the forward propeller) leaving Scotty no choice but to attempt to clear the perimeter fence at the end of the runway or face crashing into it head-on. We can infer from the video, where Scotty’s actions are clearly visible, that he was calm, clearly in control, and clearly aware that he was experiencing a power failure. We can further deduce that, as soon as Scotty cleared the perimeter fence, he began attempting to maneuver for an emergency landing in the field where the crash occurred. He had only 80-100 feet of altitude, no ability to climb, and no room to maneuver the plane into the proper attitude. These events took place in just under two seconds as he fought off one apparent stall, turn the airplane into safe landing area, with the air speed dropping below the stall speed. To an individual, those that have viewed the data and have the flight experience agree that sadly there was absolutely nothing Scotty could have done to avoid the crash. Notice above: From the Bugatti 100P project team Facebook page

Below: Excerpt from the report A witness at the airport reported that the airplane lifted off the runway. During the initial climb, the airplane banked to the right and then to the left. The airplane's left bank increased, it descended nose down, and subsequently impacted terrain inverted. Review of a chase helicopter's video was consistent with the witness statements.

PERSONNEL INFORMATION

AIRCRAFT INFORMATION Engine throttle control was accomplished through two levers installed side-by-side on the left side of the cockpit with the left throttle lever controlling the forward engine and the right throttle lever controlling the aft engine. Engagement of the hydraulic clutches on the engines was accomplished independently by two levers mounted side-by-side on the right side of the cockpit. Each engine could be run without propeller movement until the respective clutch was engaged. The airplane's maximum gross weight was listed as 2,939 pounds and its empty weight was 2,470 pounds. The airplane received its FAA Special Airworthiness Certificate in the experimental category on August 4, 2015. .........

TESTS AND RESEARCH The Onboard Image Recorder Factual Report stated that the cameras exhibited witness marks consistent with various levels of impact damage. The cameras recorded video data on micro secure data (microSD) cards. Five of the six microSD cards contained retrievable video data for the entire flight and one microSD card contained retrievable data for a portion of the flight before impact. The report, in part, described the timing and correlation of the cameras' data and the group's observations of the accident flight recorded video and a previous flight's recorded video. The description of the accident flight, in part, indicated that the pilot was in a conscious state during the recording. No pilot or ground crew conversations pertinent to the investigation were captured. All preflight activities appeared to be consistent with known procedures. The pilot was seated and belted during the recording. He moved the left/forward ignition master switch to its "on" position and depressed the starter button. Then a sound consistent with a running engine was heard and the front propeller rotated counter-clockwise. The pilot depressed the right/rear starter button. No additional engine sound was heard and the pilot moved the right/rear ignition master switch to its "on" position. The pilot then depressed the starter button again, the rear propeller spun clockwise, and the sound consistent with a running engine was heard. The pilot appeared to manipulate the area consistent with the location of the engine clutch engagement lever and the front propeller began to spin counter-clockwise. The pilot movements were consistent with flight control check. The engine and gearbox gauge indications, which included engine oil temperature, engine oil pressure, fuel pressure, water temperature, volts, gearbox oil temperature, and gearbox oil pressure for both engines were within their respective green ranges at the start of the taxi to runway 35L and through the remainder of the recording. The airplane crossed the runway edge marking for runway 35L, the pilot added power, and the airplane tracked the right side of the runway centerline. The pilot added power and the airspeed indication became alive during the takeoff roll. The airspeed was about 60 knots during the roll abeam taxiway E. The airspeed indicated 80 knots after the airplane passed abeam taxiway D. The pilot applied backpressure to the control stick when the indicated airspeed was above 80 knots. The airplane crossed abeam taxiway C and it became airborne. The left/forward throttle lever was about 3/4 knob-width behind the right/rear throttle lever. The airplane laterally transitioned from the right side of the runway centerline to the left side of the centerline. The pilot moved the gear selector switch to the "up" position, a red light nearby illuminated, and the light extinguished about five seconds later. The runway centerline was visible below and to the right of the airplane. A change in pitch was heard in the ambient engine sounds. The rpm indication for the left/forward engine began to climb and the right rear engine appeared to remain stabilized. The pilot looked downward in the cockpit area near the hydraulic valve lever. The end of runway 35L became visible and the airplane was left of runway centerline. The pilot's right arm appeared to reach in the direction of the hydraulic valve lever. The left forward throttle lever appeared to be a knob and a half width distance from the right/rear throttle lever. The left/forward rpm indications trended upward, the pilot returned his left hand to the throttles, and his right hand to the control stick. The airplane entered an uncommanded slight left roll. The left/forward engine rpm indication reached about 10,000 rpm and the pilot pulled back the left/forward throttle lever near the closed position. Engine sounds decreased, the left/forward rpm indication decreased, and the airspeed was around the start of the green arc about 70 knots. The ambient engine sound surged. The pilot appeared to have pushed the right/rear throttle forward. The left/forward engine rpm indicated an increase in rpm near its redline. The left/forward throttle lever was positioned near its closed position. The airplane exhibited an uncommanded right roll and some flutter was observed on the left aileron. The airspeed was below the green arc about 65 knots. The right roll was arrested and the airplane appeared level. About a second later, the airplane entered an uncommanded left roll. The airspeed indication was about 65 knots. The control stick was in a neutral position. The left/forward rpm indication was near redline and the right/rear engine indication was about 4.500 rpm. As the airplane rolled through 90° of left bank, the pilot placed both hands on the control stick and commanded a right roll with a positive pitch attitude. The airplane continued to roll left, the nose dropped, and a green field came into view out of the front of the windscreen. The airplane rolled inverted and the recording continued until the subsequent ground impact. The altimeter during the recording did not exhibit an increase in altitude. However, an estimate from a chase helicopter video showed that airplane reached a maximum altitude between 80 and 100 ft above ground level. Additionally, a plot of observed parameters during the accident flight video was produced. The Onboard Image Recorder Factual Report is appended to the docket associated with this investigation. An NTSB aerospace engineer, who was a member of the video group, reviewed the video recordings, assisted in observed video documentation, and produced an Airplane Performance Study. The performance study, in part, reviewed instrument readings as a function of camera elapsed time. The readings included indicated airspeed (VIAS), indicated angle-of-attack (a), left/forward and right/rear engine throttle lever angles (TLA), and the corresponding engine speeds (rpm). A plot of the tabulated TLA's, rpm's, and VIAS's as a function of camera elapsed time was produced and the data showed that the engine speed for the forward engine began increasing from 6,000 rpm about 7 seconds elapsed time without any apparent TLA input from the pilot. The pilot responded by reducing TLA for the forward engine at 31 seconds elapsed time, about two seconds before the forward engine reached its maximum operating speed (red line) of 9,500 rpm. The pilot continued to reduce TLA to a minimum of about 40° for the forward engine until, about 38 seconds elapsed time, he increased the forward TLA by 10°. The airplane's airspeed was observed decaying. The forward engine reached red line for a second time about 42 seconds elapsed time. The input TLA and engine rpm for the right/rear engine appeared more consistent than for the left/forward engine. The rpm for the rear engine remained at approximately 5,800 rpm for most of the recording until, about 31 seconds elapsed time, the pilot began increasing the rear engine TLA by 7° through the next ten seconds. During this time, the rear engine rpm remained constant despite the 7° increase in TLA. The right engine rpm reduced to about 4,500 rpm after the pilot pulled the TLA back to 45° about 41 seconds elapsed time. The airspeed plot showed that the airplane decelerated below the published stall speed of 70 knots equivalent airspeed (based on a gross weight of 2,850 lb and a normal load factor of 1.04) about 41 seconds elapsed time and remained below the stall speed for the remainder of the recording. The video evidence reflected a sequence of events consistent with an aerodynamic stall. The performance study used the tabulated airspeed and an estimated operational gross weight of 2,650 lb and determined the airplane lift coefficient that was extracted from the data as a function of indicated angle-of-attack. Where angle of attack data was available, the lift from the observed accident data compared consistently with design estimates derived by the Le Reve Bleu team. The Airplane Performance Study is appended to the docket associated with this investigation.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

|

June 4, 2017

Last week I heard from my friend Daniel Lapp in Molsheim that a permanent memorial for Scotty Wilson, the valiant builder and pilot of the replica Bugatti 100P raceplane who so tragically crashed last summer, has been set-up in Molsheim. Today I received the photographs presented above and below.

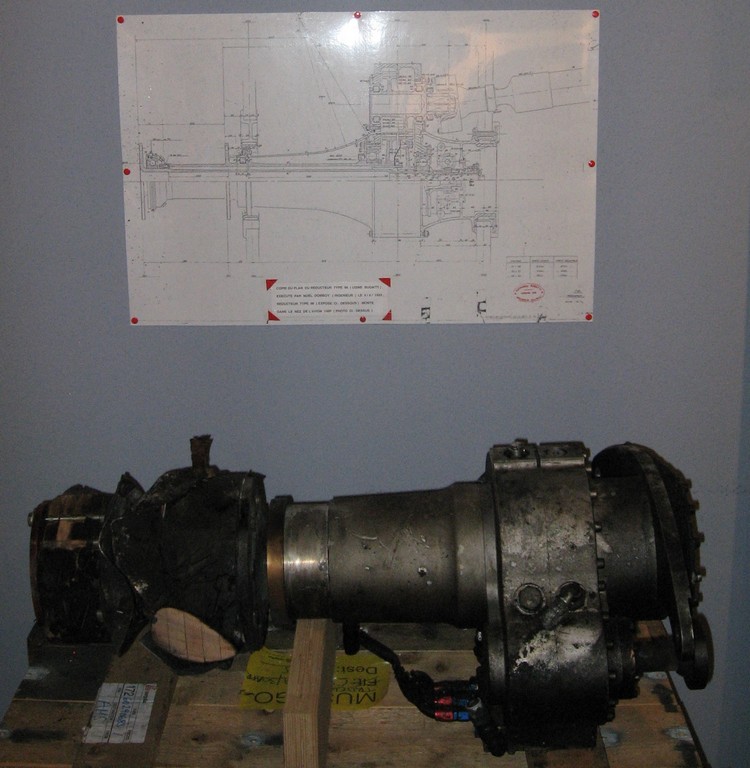

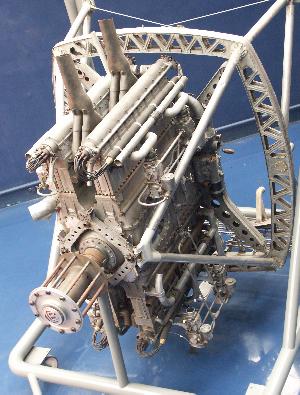

The center of the memorial is the actual reduction gearbox from the nose of the airplane, even more impressive because it still has all the marks of the burnt-out airplane. Above the gearbox is a copy of the original drawing for the gearbox, which was designed by Noël Domboy in 1938. A copy of this drawing was presented to Scotty Wilson at the Molsheim Festival in September 2015, a little less than a year before the crash.

The memorial is at the "Fondation Bugatti", which is inside the Chartreuse museum, open to the public on most days, during the summer season.

Flyer for the Chartreuse museum, with location details and opening times.

April 29, 2017

I know that you, as all of us, are interested in the real cause for the crash of Scotty Wilson in his replica Bugatti airplane, on August 6, 2016. A crash which shocked us all. On this webpage, I chose to never publish about the various theories which exist, as they are partly based on speculation.

This crash is, as all crashes in the USA, subject of a formal investigation by the NTSB - National Transportation Safety Board.

Though there are no real results yet, there is a webpage where any new information will be posted. Also preliminary reports are available. The NTSB Identification is: CEN16FA307; Aircraft: WILSON BUGATTI-DEMONGE 100P, registration: N110PX. Before the final results are published, over a year may pass from the date of the accident.

The following can be found:

February 19, 2017

Recently we could buy a Lumière - Brevet de Monge - propeller, well, at least a part of it, the part including the logo.

It is a large piece, measuring about 80 cm in length, which makes that the entire propeller would be at least 2,40, maybe even 3 metres. The maximum width is 19,5 cm.

Unluckily, we do not know (yet) where it came from. Though we do know that it must have been a big engine which it was attached to.

October 18, 2016

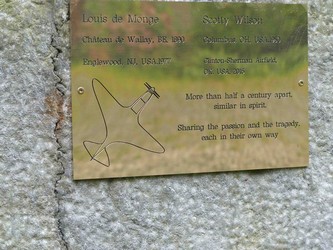

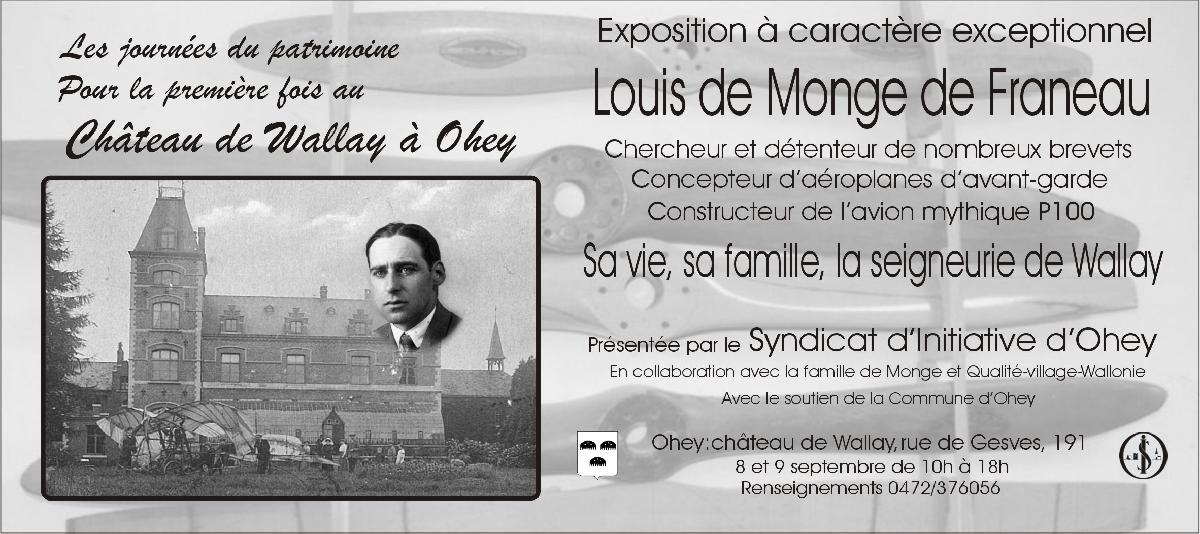

The Bugatti Aircraft Association organised a meeting at the Château the Wallay, in Ohey, Belgium, the birthplace of Louis de Monge, the aeronautics engineer who designed the Bugatti 100P raceplane. Though the meeting had been planned long before, it became a very special meeting in honour of Scotty Wilson, who had a fatal crash in his replica of the Bugatti, on August 6.

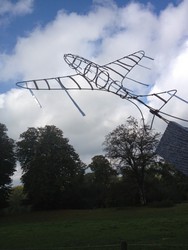

Most special was the sculpture to remember Scotty, made by Ladislas de Monge, little nephew of Louis de Monge and sculptor by profession. The BAA members shared their experiences and memories they had with Scotty Wilson

Top Photo: Ladislas de Monge explaining about the sculpture he made.

Above: The rear of the long stone has the coordinates of Burns Flat engraved, the crash site. Detail of the sculpted plane. Inside the plane there are two small metal birds. The plaque on the sculpture, which commemorates Scotty Wilson, as well as Louis de Monge. Photograph that Ladislas received; Scotty Wilson, 4 years old...

Ladislas de Monge cited (in French) the poem "High Flight" by US pilot John Gillespie Magee. Afterwards, Dick Ploeg cited the poem in English:

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace.

Where never lark, or even eagle flew —

And, while with silent, lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

– Put out my hand, and touched the face of God."

Ladislas de Monge explaining the 2nd airplane that Louis de Monge built, together with his brothers and sisters, in 1909, when he was only 19 years old. Two damaged propellers from this airplane show that, if the plane really flew, it must have been quite short. The castle is still in the hands of the de Monge family, with Ladislas' sister Véronique now living there with her husband Michel.

Paul-Benoît and Ladislas de Monge in the small Brescia Bugatti, two of the Brescia engines were used in the de Monge 7.5 flying wing airplane of 1921. A small exhibition with various original items from the time that Louis de Monge was successfully building airplanes.

The audience during the remembrance, and at several other times during the meeting. Kjeld Jessen took his Bugatti Brescia with him, for all members to admire, and enjoy! There were 10 BAA members present, plus many members of the de Monge family.

The meeting was a good memory to honour Scotty Wilson in the first place, but also to share experiences and knowledge. BAA president Jaap Horst held a speech about the post war activities of Louis de Monge, when he was in the USA. Info that the family did not yet know. Finally there was a positive conclusion to the day, when Jaap told the family that their great uncle had been working on the aerodynamics of the Bugatti that won the le Mans 24 hours in 1939. Aerodynamic feautures that were very advanced, much more advanced than on the le Mans winner of two years earlier, and in fact no racecars with such advanced aerodynamics were built until the 1970's...

Thanks to the de Monge family, and especially to Véronique, Ariane and Ladislas.

September 1, 2016

A Memorial Service with Military Honors will be held for Lt Col Scott E. Wilson, USAF (Ret), who tragically passed away on August 6, 2016.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Scotty Wilson Bugatti 100P Legacy Fund administered by Le Reve Blue LLC, dedicated to Scotty’s memory and the preservation of the Bugatti 100P Project, by clicking on the donate button on the Bugatti100P.aero website, or to the Gary Sinise Foundation at www.garysinisefoundation.org.

August 11, 2016

A video made by KFOR circulates on the Internet of the start of the last flight of Scotty in his magnificent airplane. I wasn't going to post it here, as I thought some of the images are too shocking. Therefore I made a revised version, which I post here. Click on the links below

Newsitem with comments, pre-flight preparations and more.

June 2, 2016

This is a short footage of "France's Battleship of the air" !, by British Pathé, which includes some pre-take off shots, the actual take-off, a lot of flight footage and even some, very vague, footage from inside the airplane.

Click here to see the footage of the Dyle & Bacalan DB10 taking off and in flight.

Click here to see the footage on Youtube

December 12, 2015

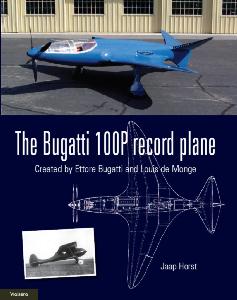

The 2nd edition, with a few improvements and changes, is now available, for only 38.95 euro!

See here for more info, and to order

Title: The Bugatti 100P record plane

Created by Ettore Bugatti and Louis de Monge

2nd edition Jaap Horst

December 8, 2015

The Bugatti 100P replica team has a new website, with a new address: Bugatti100P.AERO

August 26, 2015

Interview with Ladislas de Monge and Pierre de Bellefroid, filmmaker, in an interview on the French channel TV5 Monde (In French).

Entretien avec Ladislas de Monge, neveu de Louis De Monge et Pierre de Bellefroid, réalisateur.

Ettore Bugatti fût l'un des pionniers de l'automobile mais il rêvait aussi d'aviation. Avec Louis de Monge, ingénieur belge, il avait conçu un avion révolutionnaire qui n'a jamais volé. Ce prototype a eu un destin rocambolesque et aujourd'hui le rêve se poursuit.

Click here or on the top picture to see the interview

August 20, 2015

Yesterday, August 19, the replica Bugatti 100P airplane built by Scotty Wilson and his team flew for the first time, at an airfield in Oklahoma. I was very to be present at the first tests at this airfield, but had to leace a couple of days before the real first flight.

This is what Scotty himself said about this:

We intended this flight to be limited to a short hop down the runway to check power required/power available and to check control responsiveness in all three axes. Preflight preparation and before-takeoff checks were normal. Takeoff was normal and at a predetermined reduced power (80%) setting; takeoff roll was 3000 feet and I became airborne at 90 knots. I climbed to 100 AGL to check power and control responsiveness. The plane responded as expected to all power changes and control inputs. Maximum airspeed was 110 knots.

I reduced power for landing but the airplane floated much more than we anticipated. I landed further down the runway than planned but with sufficient distance to stop the plane. Unfortunately, I lost the right brake and the airplane departed the left side of the runway at slow speed. Due to heavy rains the night before, the ground was soft and the airplane tipped upward on its nose, damaging the spinner and both props.

Such is the nature of flight testing a new design. The relevant news is we successfully flew the Bugatti 100P for the first time. The plane flew beautifully.

July 24, 2015

Click here to see the footage, the Breguet Dorand can be seen at 9.35 min.

Click here to see the footage on Youtube

July 24, 2015

April 29, 2015

Those of you who follow the project already know this, the engines in the Bugatti 100P replica built by Scotty Wilson and his team are running! Click on the above image to see and hear it.

Scotty's comment: "On April 2, 2015 we fired up the engines and powered the drive train for the first time, with successful results. Both engines started easily and all systems - fuel; electrical; lubrication; propeller-reduction gearbox lubrication and cooling; engine coolant; and all gauges worked correctly. We kept engine and propeller RPM at reduced RPMs for this test. We noticed no unusual noises or vibration issues, but don't expect to see any until we hit the higher RPM ranges.

Next we'll mount the fuselage to the wing and install the propellers in preparation for easing into the full power engine runs."

Of course, we know that the engines are not the 4,7 litre 480 HP straight-eights as used in the original, but this is an important step in bringing the plane closer to flying!

And; Bugattis own 1.5 litre 4 cylinder engines were also used, in the de Monge 7.5 flying wing. They were of the same displacement, though less powerful..

December 27, 2014

The "man behind the curtain" attending to the engines is good friend Rex Johnson, a retired USAF Chief Master Sergeant and quite possibly the world's best airplane mechanic. The "Chief" is always right!

September 11, 2014

The complete article can be read online, and includes various photographs.

Go to www.airspacemag.com to read the article (3 pages, one has to click through).

Also on the same site are various sketches and drawings of the Bugatti 100P airplane.

February 11, 2014

February 11, 2014 Recreation of Rare Airplane to Take Flight following its Display in Southern California

Oxnard, Calif. (February 10, 2014) – The Mullin Automotive Museum, a Southern California institution devoted to the preservation of French art and automobiles from the Art Deco era, today announced it will debut the completed recreation of the Bugatti 100P airplane as part of its Art of Bugatti exhibition, a tribute to the Bugatti family’s enduring genius, opening March 25, 2014.

Originally designed in collaboration with Ettore Bugatti and Belgian engineer Louis de Monge, the original 1937 Bugatti 100P is considered by many to be one of the most technologically-advanced airplanes of the era. The 100P featured cutting-edge aerodynamics with forward pitched wings, a zero-drag cooling system, and computer-directed flight controls, all predating the development of the best Allied fighters of World War II. Powered by twin 450-hp engines, the plane was designed to reach speeds approaching 500mph, a feat previously only achieved by aircraft with twice the horsepower. The 100P was also much more compact than most aircraft of the era, with a wingspan of nearly 27-feet and an overall length of approximately 25.25-feet. In June 1940, Bugatti stopped work on the 100P and concealed the plane to prevent its discovery by the German military. Though the plane survived the war, it was left in a condition unfit for flight.

In 2009, Scott Wilson, John Lawson and Simon Birney of Le Reve Blue began construction on the first ever recreation of the Bugatti 100P. Handcrafted using largely the same materials and processes as the original, the recreation is dimensionally and aerodynamically identical to the original plane and includes elements of the five patents that Bugatti was originally awarded for the 100P. The recreation was teased as under construction at AirVenture in Oshkosh, Wis. in 2011, but will be seen as completed for the first time at the Mullin Automotive Museum, beginning in March 2014.

“We’ve searched for years to gather the best examples of the Bugatti family’s work and couldn’t be more thrilled to host the 100P at our museum,” said Peter Mullin, Founder and Chairman of the Mullin Automotive Museum. “Bugatti has always been known for their remarkable automobiles, but the 100P is one of the missing pieces that truly shows the breadth and depth of the family’s work.”

“There isn’t a better way to finish this project than to have the 100P be a part of the Art of Bugatti before it takes to the skies,” said Scott Wilson, Le Reve Blue Managing Director. “For the first time, this incredible piece of engineering and design will receive the broad recognition it deserves, 77 years later.”

The Bugatti 100P aircraft will be on display among the largest assembled collection of Bugatti artifacts and automobiles at the Art of Bugatti exhibition, opening March 2014. For further information on the Art of Bugatti at the Mullin Automotive Museum, please log onto www.mullinautomotivemuseum.com.

About the Mullin Automotive Museum

The Mullin Automotive Museum is a facility that pays homage to the art deco and machine age design eras (1918-1941) that produced exquisite art and magnificent automobiles. It officially opened its doors for the first time in the beach community of Oxnard, Calif., in spring 2010. For more information, please log onto .

www.mullinautomotivemuseum.com

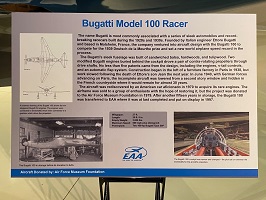

John Mellberg recently visited the EAA’s Air Venture Museum. The 100P has been moved to be included in the display of ’30’s Air Racers, and is better located than where it had been, back in a dark corner of the Museum. See pictures below.

January 4, 2014

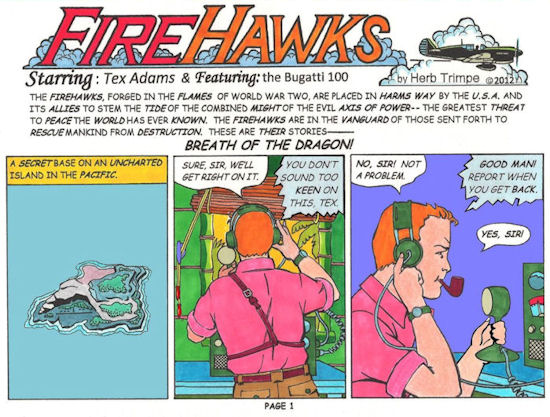

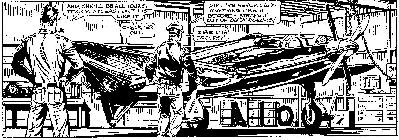

January 4, 2014 Following the publication of the first "Firehawks" comic four years ago, I now published the 2nd story. It is, as the first, written and drawn by long-time professional drawing-artist (of eg. the Hulk and other comics), Bugatti and Bugatti Airplane enthusiast and BAA member Herb Trimpe. In the story an imaginary American fighter version (Not called the Bugatti-King, I'm afraid) of the Bugatti 100P airplane plays the main role.

It is different in format to the first comic book, there are more pages, though in a smaller size and this time in Full-colour, not B&W!

The comic is now published in an exclusive limited edition: Click here for more details and direct ordering.

December 13, 2013 EAA WRIGHT BROTHERS MEMORIAL BANQUET - Bugatti 100P Presentation Oshkosh, USA

The effort to recreate one of aviation history’s most beautiful but unproven designs will be the highlight presentation at EAA’s annual Wright Brothers Memorial Banquet. This year’s banquet will commemorate the 110th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C.

Join us as EAA member Scotty Wilson describes his quest to build a full-scale, flyable reproduction of the Bugatti 100P racer, “the most historically significant airplane that never flew.”

Tickets for the banquet are $50 for EAA members and guest, $60 for non-members/guest, and include the reception, full-service dinner, and evening program.

More info at airventuremuseum.org

More than 70 years after Bugatti’s only aircraft was hidden from the Nazis a painstaking reproduction of this never-flown plane is poised to take to the skies. Jon Excell reports.

Paris. 1940. And with German forces advancing on the French capital, an advanced new aircraft is smuggled quietly out of the city before it can fall into enemy hands.

A vivid shade of blue and startlingly futuristic, the aircraft in question was the Bugatti 100P, the only plane built by legendary car manufacturer Ettore Bugatti.

Boasting a highly streamlined forward-swept wing design and using two cleverly placed engines to drive contra-rotating propellers, the 100P featured a host of innovations that made it one of the most technologically advanced aircraft of its time.

War broke out before the plane could be flown, but Bugatti’s chief engineer on the project, Louis De Monge, projected a top speed of 500mph.

Had the Germans got hold of it — and there’s anecdotal evidence that Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister for production, was aware of the plane — it could have wiped out the aerial advantage of the spitfire and had a profound influence on the outcome of the war.

Fortunately this never happened. The aircraft remained hidden and what remains of the original resides at the AirVenture museum in Oskosh, Wisconsin. It’s too fragile and missing too many components to fly.

But over the years the plane has continued to exert a spell over engineers, who, beguiled by its Art Deco beauty and the mystery of its untested prowess, have long wondered how it would have performed.

Later this summer, a team led by retired US fighter pilot Scotty Wilson hopes to find the answer to this question when its reproduction version of Bugatti’s landmark plane takes to the sky for the first time.

The project has generated plenty of excitement, not least among the enthusiasts who’ve contributed $65,000 of funding via the Kickstarter crowd-funding site. Some of the more prominent supporters include McLaren design chief Frank Stephenson and US chat show host Jay Leno, who is rumoured to be interested in buying the finished aircraft. But perhaps its biggest champions are the engineers behind the project: a team drawn together by a shared fascination with the aircraft and a deep respect for De Monge.

This aeroplane was designed by a guy with a slide rule and pencil in 1937,’ said John Lawson, the project’s engineering director, ‘and some of the stuff he did in that day was absolutely revolutionary.’

This aeroplane was designed by a guy with a slide rule and pencil in 1937,’ said John Lawson, the project’s engineering director, ‘and some of the stuff he did in that day was absolutely revolutionary.’

Detailing some of the innovations made by De Monge, Lawson — who is the MD of UK firm Lawson Modelmakers — explained that one of the keys to the aircraft’s projected performance was a novel cooling system based on observations made by English engineer Frederick Meredith.

‘Meredith discovered that if you pull cooling air in through a high-pressure area on the aircraft and duct it through the radiator, if the channelling is the right size as it exits the radiator it expands and you get negative drag — and at certain speeds you get positive thrust,’ he explained.

It’s long been thought the P51 Mustang was the first aircraft to make use of the “Meredith effect” and the discovery that De Monge was a few years ahead of US engineers has, said Lawson, prompted a rewriting of the aviation history books. ‘We had a long argument with the P51 Mustang society, he said. ‘They were adamant that this had been created for the Mustang until we showed them the patents from 1937.’

Another innovation that was ahead of its time was De Monge’s use of simple analogue sensors to detect the aircraft’s flight phase and automatically adjust the flap and undercarriage system. ‘It knew from what these sensors were telling it what phase of flight it was in,’ said Lawson. ‘For instance, if you were sat on the ground with no airspeed and you opened up the throttle it knew you were trying to take off so would automatically set the flaps in the take-off position. Likewise when you come in to land and start to throttle back and slow down it realised you wanted to land so it would put the flaps and the wheels down.’

Lawson added that the aircraft’s balsa sandwich construction made it one of the first composite planes. ‘It had poplar on the inside, hardwood on the outside and balsa in the middle. That made it very light and very strong.’

But with many of the original blueprints destroyed as the Germans advanced on Paris, recreating the aircraft has been an exercise in engineering detective work and the team has relied on a handful of remaining drawings and careful measurements of the surviving plane in order to determine exactly how de Monge and his team designed and built the original.

The gearbox, Lawson’s biggest contribution to the project, is a case in point. ‘So little information exists on this,’ he said. ‘There are no drawings apart from an installation drawing, which basically gives you a side profile.’

‘We started by reverse engineering the original box from the photos we had. Luckily someone had taken a load of photographs of one of the spares and he’d put a rule into the picture.’

The team frequently had to improvise however. ‘On the original gearbox the last set of bearings are on the nose of the gearbox itself so the forward propshaft comes out through the rear propshaft unsupported,’ he said.‘That’s fine if you’re going straight and level, but the minute you start pulling any g that little thin propshaft is just going to just bend. So I put a pair of ceramic bearings right up in the nose of the rear propshaft.’

Lawson is keen not to take all the credit for the finished gearbox — which is now being installed in the plane along with the engines, drive lines and flight-control systems — and pointed to valuable help from Vocis, the UK transmission specialist behind the gearbox for the McLaren MP412C and the Lamborghini Aventador.

The team faced a similar challenge when designing the wings and travelled to Oskosh to digitally measure the wing on the surviving aircraft. Models based on these measurements have since been run through a simulator in order to determine how the plane will fly, a luxury that wouldn’t have been available to De Monge. ‘The initial indications we’re getting out are that it will fly very well: it’s got a pretty neutral centre of gravity…because the rear engine can move backwards and forwards we can put the centre of gravity wherever we want.’

The team faced a similar challenge when designing the wings and travelled to Oskosh to digitally measure the wing on the surviving aircraft. Models based on these measurements have since been run through a simulator in order to determine how the plane will fly, a luxury that wouldn’t have been available to De Monge. ‘The initial indications we’re getting out are that it will fly very well: it’s got a pretty neutral centre of gravity…because the rear engine can move backwards and forwards we can put the centre of gravity wherever we want.’

With a limited amount of original design detail to go on, the new aircraft does differ from the original in a number of areas. For instance, it uses Suzuki motorcycle engines rather then Bugatti engines, the oil-cooler duct is in a different position and the contra-rotating propellers were designed from scratch by UK firm Hercules. ‘No one can ever build a replica because not enough information on the original exists,’ said Lawson. ‘What we’re building is a reproduction that is accurate in all the key areas and only changes where we’ve had no choice but to change it.’

The group is gearing up to fly the aircraft for the first time later this summer in the US and a European tour will hopefully follow. ‘We want to bring it to Europe. We want to fly in Europe,’ said Lawson. ‘We want to let people in Europe see it — we want to inspire engineers.’

After that, it’s likely that the aircraft will be sold. Although if it flies well, Lawson doesn’t rule out the possibility of making another aircraft. ‘We would consider making another one,’ he said, ‘but we’d probably make it entirely in modern materials so that we could make it quickly.’

The Bugatti 100P project is quite close to completion, but funding is getting tight, that's why Scotty Wilson uses this novel "crowd funding" method to be able to complete this dream of an aeroplane. In his words:

We’ve worked hard for over three years to bring Bugatti’s “Blue Dream” to life. Some of you have followed our progress from the beginning; others are relative newcomers. We appreciate all of your kind words and encouragement. You remind us often that some dreams are so big and so bold they span oceans, decades, and lifetimes. Bugatti’s “Rêve Bleu” is one such dream.

We need your help and want to offer you a meaningful way to participate as we enter the final stage of this project. If every one of our website and Facebook fans passes this along to every one of their Facebook and other “Friends” we’ll reach our goals.

Please join with us on what promises to be an eventful final leg of this journey. See more at Kickstarter by following this link:

With your help, we can change history!

Update: The initiative raised more than the $50,000 goal, thanks to you all!

August 22, 2012

August 22, 2012 On September 8 and 9 (from 10 - 18 h) there will be an exposition in the deMonge family castle (chateau de Wallay) at the rue de Gesves 191, Ohey, Belgium.

Apart from the exploits of Louis de Monge and the Bugatti 100P, there will be other expositions about other family members, and the castle history

March 18, 2012

From the RPE Press Office:

"Radical Performance Engines is pleased to confirm its association with the Bugatti 100P project, a recreation of the most advanced aircraft of the 1930s, by supplying two RPE 1500cc powerplants and technical support to the project.

The Bugatti 100P Projects’ aim is to bring to the skies a reproduction of the original Bugatti 100P airplane, an elegant design that sadly never saw the light of day due to the outbreak of WW2. A dedicated team of volunteers has painstakingly constructed the airframe, working towards a completion date at the end of the year. The Bugatti 100P featured a number of ground-breaking techniques, including dramatic, forward-swept wings, counter-rotating propellers and automatic wing-flaps.

RPE will supply two 1500cc, 260bhp four-cylinder engines to the project, highly-compact engines that are situated in the fuselage behind the pilot and connected to the nose mounted gearbox with driveshaft’s that run below the pilots elbows. The same engine design is well-proven, used in Radical Sportscars' best-selling SR3 RS racecar, in production for over a decade. Just like the original, the new Bugatti 100P will be using a race-proven engine, albeit this time controlled by an advanced engine management system with full data logging.

"RPE is extremely proud to be assisting the Bugatti 100P Project on this exciting venture, bringing one of the most distinctive aero shapes of the 30's to the skies at last," said RPE General Manager, James Williams. "With RPE power, the Bugatti 100P can exhibit the same outstanding performance and manoeuvrability that was envisaged for the aircraft over 70 years ago."

Radical Performance Engines are the world’s leading small-capacity racing engine and drive system specialists. With over thirty years’ experience in engine tuning, Radical Performance Engines has established an enviable reputation in the design and production of an increasing range of four and eight-cylinder race engines, all of which are built and developed in-house. Such is RPE’s confidence in the reliability of the engine work it carries out, much is covered by a warranty for 40 racing hours; no other manufacturer at this level of motorsport offers such cover."

For more media information contact: Will Brown, Radical Group Press Office: +44 (0)1733 331616

I have not been updating the news on Scotty Wilson's replica project often, as it is much more convenient and informative to follow progress on his own website: bugatti100p.com. The advances are considerable though, with detailing going on for the cockpit, the wings and all other parts needed. However, the decision to switch to single piece propellers needed a redesign of the gearbox, thus setting the project back by several months. See some of the pictures below.

Meanwhile, Scotty also found the time to come to the European Airshow Convention in Brussels (February 23-25) and hold a lecture: "The Bugatti Project: from drawing board to flying display."

18 February 2012:

Fitting canopy attachment

Another view of canopy and cockpit

Landing Gear after plating

Wing

Shop (North End) on 17 Feb 2012

14 February 2012:

Many of the gearbox components are shown in this image. Progress is now well advanced on the manufacture with the shafts currently undertgoing final machining, gears and minor shafts out for heat treating and all bearings and seals with the manufacturer.

2nd February 2012:

Casings loose assembled to check for fit and tolerance.

September 13, 2011

I'm very sorry to announce that Jean Sibille died on September 2, at the respectable age of 87, his son Jean-François Sibille recently sent the notice of his father's passing. Jean leaves three children, grandchildren and great grandchildren.

On the picture above Jean Sibille can be seen seated on the left, the person standing being Jean-Louis Arbey. The picture was taken by Michael Firczuk in 2001

Jean Sibille was a 15 year old apprentice draftsman who in the late 1930s worked for Louis de Monge. He was the very last person still alive who was there at the workshop when the Bugatti 100P was being built. He contributed to the knowledge about the 100P significantly by sharing with us many details that no one else could have possibly known. For example, he knew – and we later confirmed – that the cockpit was not painted red; the engines were never started once installed in the plane; and that Bernard de Romanet’s widow was a frequent visitor (though it may be also that she was in fact Louis de Monge's secretary, as there was a Madame de Romanet on the payroll.)

Furthermore, Jean Sibille made a few drawings depicting the workshop layout, as well as the drawing room with all people present.

Several BAA members met with Jean Sibille, like Michael Firczuk and Jean-Louis Arbey, while others like Frederic Gasson talked extensively with him on the phone. Ladislas de Monge met with Mr. Sibille recently in his home.

August 7, 2011

The Bugatti 100P replica was presented from July 25 - 31 at the Oskosh Airventure 2011, and attracted lot's of attention, as can be seen on the top left picture, on the right the airplane as it was just before the show.

Appreciation was great especially for showing an unfinished airplane, where the build principle and other details could be still seen.

August 7, 2011

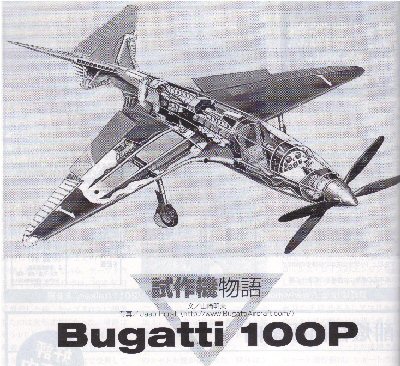

The Japanese monthly magazine Aireview (since 1951) features a 8-page article on the Bugatti 100P, in it's September 2011 issue. Author Ken'Ichi Sunohara received some assistance from the BAA.

However, it is impossible for me to read the contents, as the only characters that one can recognise are the numbers. From these numbers however, it can be seen that the article starts with a general history of Bugatti, and mentions the WW1 aero engines. There is of course a description of the airplane itself, and the Scotty Wilson replica project is mentioned, including a picture of Wilson and Carlson measuring the airfoil on the original airplane.

The article also mentions the NACA 23012 airfoil as measured, and the Durakore material that Scotty uses for the replica.

Scotty Wilson works to build a Bugatti 100P aircraft in a hangar at Harvey Young Airport in east Tulsa.

Group rebuilds piece of aviation history with Bugatti 100P reproduction

They did a pretty good job with the print article; the video is exceptionally good considering the esoteric subject matter.

However, as usual, the press never gets everything right. They left off several sponsor and partner names; they have Ladislas being a former fighter pilot!

Go to tulsaworld.com for the article plus video.

Futher info about Scotty Wilson's replica project, in newsletter no. 3, go to bugatti100p.com

Oklahoma Man's Bugatti Plane Replica A Journey of Discovery - NewsOn6.com - Tulsa, go to newson6.com

Futher info about Scotty Wilson's replica project, in two newsletters, go to bugatti100p.com

Above an image as the airplane is now, with wing spars installed.

John R Lawson made a new website for Scotty Wilson's replica project, go to: bugatti100p.com

December 9, 2009

December 9, 2009 Long-time professional drawing-artist (of eg. the Hulk and other comics), Bugatti and Bugatti Airplane enthusiast and BAA member Herb Trimpe made a comic strip "Firehawks" in which the Bugatti 100P airplane plays the main role.

I won't give any details on the story, I'll just tell you that it is both interesting and exiting.

The comic is now published: more details!

Scotty Wilson (left) and Gregg Carlson use the Profiler to collect data on the Bugatti’s wing. |

Members aim to replicate, fly acclaimed aircraft

Two Oklahoma EAA (Experimental Aircraft Association) members are breathing new life into one of aviation history’s most beautiful but unproven designs, the Bugatti Model 100 Racer. This sleek machine was built by famed automobile maker Ettore Bugatti and engineer Louis de Monge to compete in an air race before the outbreak of World War II, but it wasn’t finished in time. When the German army marched on Paris in June 1940, the project was abandoned before the airplane ever flew.

But Scotty Wilson, EAA 572551, and Gregg Carlson, EAA 1015379, are on a mission to change that.

The two flew from Tulsa to Oshkosh this week to examine the genuine article – the Bugatti Racer airframe donated to EAA in 1996 that’s on prominent display next to EAA’s Spirit of St. Louis replica in the EAA AirVenture Museum. In particular, they’re trying to identify the NACA equivalent airfoil Bugatti used by using what they call the Profiler, an electronic plotter that rolls along the wing’s surface transferring data to a computer for analysis.

“There is disagreement among enthusiasts regarding the airfoil,” said Wilson, a retired U.S. Air Force fighter pilot who now flies a Lancair 360. “The discussion ranges widely – and wildly – from an Eiffel 317 (definitely not, he said) to the equivalent of a NACA 21112.1 with reflexed meanline (Wilson’s choice).”

A full view of the Bugatti Model 100 Racer.

A full view of the Bugatti Model 100 Racer.

|

Some aviation enthusiasts insist that since the aircraft has never flown, it is not historically significant, but Scotty Wilson vehemently disagrees. “There were five patents issued to Bugatti for the airplane – many of which appeared on other aircraft after the war,” he said, including the dual drive train, the flight control tail that mixes the elevator and the rudder, and the automatic flaps system, which pre-dates the F-16’s by 40 years.

The fact that it has never flown makes the project a unique challenge. The reasons against building it – it never flew, no drawings, etc. – also present a research challenge. It is their intention to honor the original builders by making a true copy. To do that they need to profile the wing to determine the airfoil.

The current status of the Bugatti replica fuselage, which its builders intend to have finished by next spring.

The current status of the Bugatti replica fuselage, which its builders intend to have finished by next spring.

|

Regarding the engines, Bugatti designed the airplane to use two of his famous 50B engines modified for aircraft use, turning two metal, ground-adjustable, contra-rotating Ratier propellers. The two original 50Bs still exist, and Wilson and Carlson have seen one of them – in South Carolina. The other is in England.

The replica racer is being built so it could accommodate 50B replica engines, but the likely powerplants will be two late-1990s/early 2000s BMW engines.

No one could tackle a project of this importance and complexity without assistance, and Wilson and Carlson are quick to acknowledge those who have been most helpful. For example, they credit EAA’s restoration photographs along with those of Michael Firczuk as being crucial to the effort. “We also owe thanks to our European friends, Jaap Horst and Frederic Gasson. They are among the most knowledgeable – and unselfish – people with whom we’ve had the pleasure to work,” Wilson said.

Original article from www.eaa.org.

September 18, 2009

September 18, 2009 Scotty Wilson and Gregg Carlson started the build of a replica of the Bugatti 100P airplane this summer. The following text is from Scotty Wilson:

My good friend Gregg Carlson and I first discussed building a replica Bugatti 100P one year ago. We concluded after several months of research that we could and should build the plane. We knew there would be challenges because the plane is such a devilish mixture of simplicity and complexity. And, with so many gaps in the historical record, we just had to accept the fact that we would not be able to answer every question. At some point, we would be faced with a choice: move forward or succumb to paralysis by analysis.

We chose to move forward, and are building a replica as faithful to the original as is practical.

With many thanks to several BAA members, we have finished our preliminary design studies, assembled an international team of enthusiasts, and are well along with assembling the fuselage. We began planking the fuselage with a balsa/hardwood product yesterday, and will have the fuselage shell essentially completed by the end of September. This is a bit behind our original schedule but we are on track to fly the plane in the Spring of 2011.

The design lends itself nicely to being built upside-down (see photographs). We’ve attached the balsa/hardwood sandwich planks (approximately 30mm wide) to the permanent bulkheads and longerons and to the temporary formers. Once we’ve covered the entire fuselage, we will follow with epoxy between the planks and then cover the exterior with fiberglass. Once the fiberglass covering is cured, we will turn the fuselage right-side up and put it in a cradle. We will then remove all temporary formers, fiberglass the inside surface, and install the remaining permanent bulkheads, doublers, and other supporting structure.

The design lends itself nicely to being built upside-down (see photographs). We’ve attached the balsa/hardwood sandwich planks (approximately 30mm wide) to the permanent bulkheads and longerons and to the temporary formers. Once we’ve covered the entire fuselage, we will follow with epoxy between the planks and then cover the exterior with fiberglass. Once the fiberglass covering is cured, we will turn the fuselage right-side up and put it in a cradle. We will then remove all temporary formers, fiberglass the inside surface, and install the remaining permanent bulkheads, doublers, and other supporting structure.

The rear two fuselage bulkheads are part of the plane’s permanent structure, as are the longerons. We felt it necessary to permanently affix the planks securely to the aft bulkheads while the plane was in the jig, so to ensure proper alignment of the tail surfaces.

We will have a website up soon so that those interested in the project can follow our progress.

December 30, 2008

December 30, 2008 Long-time professional drawing-artist (of eg. the Hulk and other comics), Bugatti and Bugatti Airplane enthusiast and BAA member Herb Trimpe made a comic strip "Spitfire" in which the Bugatti 100P airplane plays the main role.

I won't give any details on the story, I'll just tell you that it is both interesting and exiting.

The comic will be published by Image Comics of Berkeley, California, USA. It will probably be published together with several other comics in one booklet / magazine.

December 13, 2008

December 13, 2008 The Dutch / Belgian branch of the Bugatti Aircraft Association had a successfull first meeting on November 29. As an appropriate location we chose the private Bugatti museum of Jean Prick, son of the famous "Bugatti Pope" Guillaume Prick, who played in important role in the early Bugatti club organisation.

Present were 5 members, plus 3 interested Bugattists of whom two became members of the BAA (At last, Frans!) after the meeting. On the top photo we see them from left to right: Jan Boellaard and his brother Edwin, Jeroen Vossen, Jean Prick (sitting down holding the original print of the T67 engine), Martijn Visser, Jaap Horst and Frans Hofman (below) and Bart Rosman.

We were kindly welcomed by Jean, and after a small introdcution and some discussion about the BAA organisation and recent developments, there were two presentations. One by Jaap, about the Bugatti Airplane. This presentation was largely based on the presentations by Philippe Ricco and Frederic Gasson in February of this year, at the Retromobile in Paris. After this there was a very interesting presentation by Martijn Visser, on all Bugatti boats (the Niniette's, the airplane engined power racers, the torpedo boats and the "Barbara III" sailboat. A lot of new information and pictures were presented by Martijn.

After this, we had a tour through Jean's museum, where the result of over half a century of collecting Bugatti items is very remarkable indeed. Below a picture, giving a small impression of what can be seen!

The day was concluded with a very nice dinner in a nearby restaurant.

Forum on the 100P at the secretprojects site, with various comments, including a redesign of a fighter version of the 100P, using a Bugatti T67 V-16 engine:

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,1100.0.html

Forum on model-building a 100P, various pages. In Dutch, but with interesting photographs:

http://www.modelbouwforum.nl/forums/vliegende-schaalmodellen/30306-bouwverslag-bugatti-100-p.html

The BAA board decided that we need a speedy way to interchange information, that's why I put the BAA file server online.

All members can view and upload here all Bugatti 100P and associated information.

Of course the file server is at this moment only partly filled, plase contribute as you can!

Access through BugattiAircraft.com - members only

Of course the information is intended for BAA members only, it is not allowed that the information will be used in any external publications, without permission from the BAA!

May 15, 2008

May 15, 2008 The BAA just received two parts, which were most probably intended for the Bugatti Airplane. The two identical parts were offered to BAA president Jaap Horst by Norbert Bukowski, to be placed on the "parts for sale" page of Jaap's Bugatti site. Jaap compared the photographs he had received from Norbert who identified the parts as "possibly T64" , with all drawings and photographs of the Bugatti Airplane that he has in his files. Jaap finally encountered one photograph from the collection of Jean Louis Arbey, who has various Bugatti airplane parts in his possession. Two similar, though slightly different, parts are shown in the photograph below.

We still do not know exactly how the engines were mounted, it seems that the engines were mounted on two rails alongside either side of the engine, these rails being attached to these engine mounts, and the engines mounts to the fuselage bulkheads.

The parts are made of aluminium, and have 2 horizontal and three vertical holes. The base width of the part is 100mm, maximum width 140mm, the height 85mm, thickness 44mm.

The distance between both big holes is 100mm, diameter 14mm. Distance between the two outer vertical holes is 70mm, diameter 11mm. The third hole is ecactly in the middle, with an ofset of 20mm.

The parts seem not to have been used at all, there are no scratches from mounting or tightening bolts or otherwise. This is nothing strange, many "double" parts are known to exist, for example all the parts in Arbey's collection are also with the plane. On the drawings of the metal parts, present in the library of the Schlumpf museum in Mulhouse, it is indicated that two item should be made. Bugatti was in fact making the parts for two airplanes, though only one airplane was really made.

So, this being the first parts, still several to go before we can put a replica of the airplane together, using original parts! How would 3 out of 5 work for an airplane?

A Forum discussion about what the fighter version of the Bugatti airplane, the 110P, might look like. Includes a drawing where the T67 16 cylinder has been put in the 100P:

www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum

And a complete (searchable) archive of all issues of the UK magazine "Flight", from the start of the magazine in 1909! Nothing on the Bugatti airplane, several items about deMonge and Breguet-Bugatti, also items about the Deutsch de la Meurthe races:

www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive

April 13, 2008

April 13, 2008 These are images of the wooden propeller of the flying-wing airplane "deMonge Type 7.5" of 1925. This airplane was powered by two Bugatti Brescia 4-cylinder engines of 1500cc each. The propeller is made by the Lumiere company, which was at that time owned by deMonge. Photographs were kindly sent to us by owner Daniel Lapp from France.

Apparently Louis deMonge, known for being the chief-designer for Ettore Bugatti's 100P air racer, made the design of this improved propeller during his military service in World War One, on a shed door which he converted into a drawing table. Aparently the design was succesfull, in being a much more efficient propeller than what was used up to that date.

This propeller was one of two that were used on the deMonge 7.5, one of the various airplanes designed and built by Louis de Monge, sometimes in cooperation with others. The 7.5 was a small flying wing design, the 7.3 being a bigger version.

The propeller has the Lumiere factory mark on it, and is inscribed on the hub; "de Monge 7.5" and "Bugatti 1500". Above on the right an image of the deMonge 7.5, showing that the fuselage has a wing profile. More about deMonge and his creations in various issues of "Pegasus"

As you may know, this association was run by myself, Jaap Horst, for 10 years now, in which period I made 18 issues of the Newsletter Pegasus, and in which period the number of members grew steadily to about 55 today.

As the BAA is an international organization, distances make it difficult to organize meetings, where people can actually see each other, and talk about the airplane. If we can make a separate branch organization for each major country, there can be meetings for each country separately. I made the following member count:

13 in Netherlands/Belgium

10 in France/Switzerland

17 in USA

8 in UK

Logically, it was decided that we need a branch in the USA, UK, French and the Netherlands. Other countries (Italy, Austria, Australia, Sweden, Switzerland) have only one or a few members each. Members of these countries can of course attend the branch meetings in other countries.

After this decision, I had contact with possible board members for each country, I had already some enthusiastic members with whom I was communicating a lot, so the board members (or directors) for the different countries are the following:

USA: John M. Mellberg of High Point, North Carolina possibly with help from his son (also John) and Michael Firczuk of Durham, New Hampshire.

France: Frederic Gasson of Sceaux (near Paris) .

Netherlands: Jaap Horst of Nieuwegein and Martijn Visser of Wilnis.

UK: Paul Nickalls of Much Wenlock, Shropshire

Contact details for the board members; further down the page.

April 7, 2008

April 7, 2008 The BAA during 10 years was mostly a paper association. Members came together once at Retromobile, and in august 2005 we organized a stand at the Dietz airshow. Between Frederic Gasson and myself rose the idea to organize again a meeting, and this time let it coincide with the Retromobile classic car show in Paris, which is held every February. Idea behind this move was that many Bugattistes, and among them quite a few BAA-members, visit Retromobile every year. A contact was made with the musée de l’Air et Espace at LeBourget airport, on the northside of Paris. However, it turned out that the museum would not give us a conference-location for free. As the BAA is not a very rich association, we could not go forward with this. Frederic contacted the Retromobile organization (Thierry Farges) which had a new possibility; the organization of conferences! In fact, for the conferences they use the location where the Bonhams auction was held. There were two downsides; the conference should be held the 2nd weekend of the Retromobile (with most BAA members going the 1st weekend), and the language of all speeches should be in French…

From then we (Frederic mainly) moved fast-forward with the organization. He invited Aviation author Philippe Ricco to hold an introduction on the airplane (My French turned out to be not too bad, but I still held my short welcome speech in English, Frederic translated it), the students of ENSICA aeronautical university in Toulouse would hold an introduction on the study they are currently performing on the 100P airplane, and Frederic would hold a talk about the future. The date was set to Saturday February 16, the next day there would be a possibility to meet at the musée de l’Air et Espace.

So, what new informations were given during the conference? In the following, a short overview of the speeches held, and the surprising aspects in the contents thereof. Photo: Frederic Gasson

Philippe Ricco - L’avion Bugatti 100P

Philippe Ricco - L’avion Bugatti 100P

The subjects covered by Philippe were the following: Evolution of French Aviation, Bugatti and aviation, Louis De Monge, Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe, Construction of the Bugatti 100P, other realisations by coworkers.

Philippe comments how in the beginning of the 20th century France was the centre of the development of aviation, with many pioneering aviators. During the first world war, airplane manufacture was industrialised. He went on about the early post war period where mainly warproducts were re-used, and the futher rationalisation and regroupement of producers that took place later in the inbetween war years..

He then focuses on the involvement of Bugatti in aviation, with the WW1 engines and the Bugatti-licensed engines. Philippe shows a lot of unknown photographs, which makes this part very interesting.

Apart from the well-known Breguet Léviathan, of which Philippe showed some hitherto unknown photographs like the one above (which is in fact a color photograph, or maybe a colored photograph) and a blueprint for this “Avion Type 20” 900hp powerplant, also the more unknown Gyroplane Laboratoire Breguet was included, with many more photographs. The Bugatti-shape radiator, as well as the outline of the 8-cilindre Breguet-Bugatti engine can be seen. See for more info Pegasus 12.

Philippe ends this story on Bugatti in aviation with a list of (french) patents, many of them already known.

The story logically continues with an overview of airplane constructions by Louis de Monge, Philippe gives the following list, and gives a few new photographs:

1914 : Buscaylet expérimental à aile « vivante »

1921 : Lumière-De Monge 5/1

1923 : Buscaylet-De Monge 5/2

1925 : De Monge 7/3

1925 : De Monge 7/5

1927 : De Monge 10-1 (Koolhoven FK-31)

1931 : De Monge 120 RN3

Especially the 1923 Buscaylet-De Monge 5/2 and the 1925 De Monge 7/3 were airplanes that I did not know of yet, and which are a very interesting addition to the history that finally led to the Bugatti 100P.

Philippe then gave an overview of the history of the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe, a Prize created in 1900 by Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe and Ernest Archdeacon. There were 5 races from 1912 to 1922 over 200, two times 200, and finally 300 km. It was recreated in 1931 by Suzanne Deutsch de la Meurthe, there were 3 races in 1933, 1934 and 1935.

Philippe Ricco goes on to the development history of the Bugatti aircraft, with the 1st 2x3.2 litre design which was not executed, the 100P, 101P (with smaller wingspan) and the 110P (the combat version). He shows a few photo’s that were not shown in Pegasus before. Also, Philippe shows new drawings, made by André Tilley. Philippe Ricco finishes with an overview of later constructions made by those that worked on the Bugatti airplane, André Stark, André Grenet and Max Holste. Especially the last was quite successful after the war.

Florent Barbes, Yannick Neubrand, Morgan Cotel, Elena Collado Morata

Étude en soufflerie du domaine de vol basses vitesses

The above students of ENSICA in Toulouse are studying the behaviour of the Bugatti 100P. This project was initiated by Frederic Gasson, who will built the 1:5 scale model (shown above) which will be used in the windtunnel tests.

Goal of the study is to increase the knowledge of especially the low-speed stability of the Bugatti airplane.

Roughly, there are 3 stages in the project:

- Preliminary study, in which the order of magnitude of the different parameters (speed, forces etc.) are estimated

- The windtunnel test itself and the preparations for this test.

- Post-test analysis: Transposition to real scale

Scale effect (Reynolds)

Geometry and speed

Turbulences

Direct analysis

Analysis using computer simulations

The windtunnel used for the testing was built in 1941, and was used for the testing of many aircraft, including the Concorde.

The windtunnel used for the testing was built in 1941, and was used for the testing of many aircraft, including the Concorde.

Results of this study will be published in Pegasus in the near future!

Frederic Gasson - Bugatti 100P revival project

Frederic Gasson goes into the post-war history of the Bugatti airplane, of course ending in the situation as it is today, in the EAA museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

He then goes into the details of the airplane, showing many interesting photographs. Shown is a period photograph of the wing, clearly showing the flaps of the Bugatti 100P airplane. Most of these were taken when the plane was being restored in Oshkosh. I was told by John Mellberg that the, now characteristic red color for the cockpit and the grey colour for the engine compartment was painted like this by Les Lefferts, to hide the bad shape that the wood of the fuselage structure was in.

Frederic continues with the history of speed records in aviation, with both the absolute records (for propeller planes) both the sea-planes as the landplanes. Interestingly, Frederic also mentions some speeds for (modern) aircraft with limited power. See table on the right. This of course also relates to his project for a flying replica of the Bugatti airplane, which, when executed in France, is easiest to get certified when the power is limited to 250HP. Knowing how he made the 1:5 RC model, this will probably be executed in carbon fibre– epoxy.

The meeting lasted for about 2 and a half hours, with approximately 50 people attending, which was quite good in fact! With thanks to Thierry Farges and the Retromobile organisation! After the conference there was vivid talk amongst all aviation and Bugatti enthusiasts.

The meeting lasted for about 2 and a half hours, with approximately 50 people attending, which was quite good in fact! With thanks to Thierry Farges and the Retromobile organisation! After the conference there was vivid talk amongst all aviation and Bugatti enthusiasts.

The following day there was a visit to the musée de l’Air et de l’Espace at Le Bourget airport, also in Paris, where about 10 people saw some of the contestants in the coupe Deutsch de le Meurthe, as well as of course the big H32 Breguet - Bugatti T32B engine shown.

NEWS

NEWS  100P Airplane

100P Airplane  Bugatti

Bugatti  de Monge

de Monge  Organisation

Organisation  Pegasus Newsletter

Pegasus Newsletter Contact

Contact  Links

Links Main

Main